Unfinished Freedom and Lingering Wounds

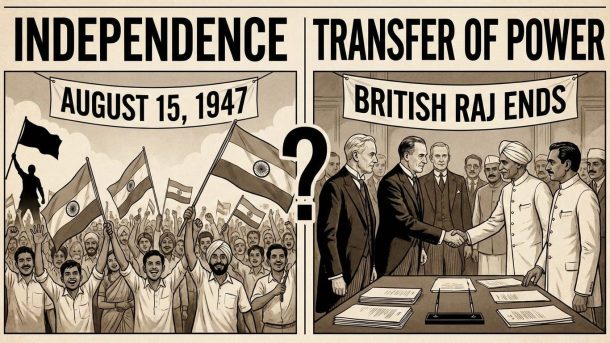

Did India truly attain independence on 15 August 1947, or was it merely a Transfer of Power by the British to a carefully chosen Indian elite? This question is not academic rhetoric. It goes to the heart of India’s continuing struggles political, psychological, institutional, and civilizational. To understand present-day India, we must revisit 1947 honestly, without colonial guilt or post‑colonial romanticism.

How Long Were We Ruled—and Controlled?

The British did not merely rule India; they reshaped it to serve imperial interests.

- Company Rule (1757–1858): After the Battle of Plassey, the East India Company began systematic economic extraction, dismantling indigenous industries, agriculture, and revenue systems.

- Crown Rule (1858–1947): After the 1857 uprising, governance shifted to the British Crown. Control became tighter, bureaucracy deeper, and cultural dominance more institutionalized.

That is nearly 190 years of direct control, and over two centuries of influence, during which India was reduced from one of the world’s largest economies to a dependent colony.

Colonialism was not merely a political occupation; it was a deep and systematic mental colonisation, one that outlived the empire itself and continues to shape the thinking, loyalties, and self-perception of many even today.

1947: Freedom or Handover?

Legally and administratively, 15 August 1947 was a transfer of power, not a civilizational liberation.

- British laws remained intact

- British-designed institutions continued

- British-trained bureaucracy took charge

- British strategic interests were carefully protected

The British exited without dismantling the systems they had created, ensuring continuity of influence. Indians took over the same colonial machinery, administering inherited laws, institutions, and governance structures with minimal structural rupture. Real independence would have required a conscious decolonisation of laws, education, governance, and strategic thinking. That fundamental transformation did not occur in 1947.

British Control Even After 1947

A telling indicator lies in India’s armed forces leadership.

- Army Chief: British until 1953

- Navy Chief: British until 1958

- Air Force Chief: British until 1954

For years after “independence,” India’s sovereignty in defence was symbolic rather than absolute. Strategic doctrines, training methods, and command culture remained colonial.

For years after so-called “independence,” India’s sovereignty in defence was symbolic rather than absolute. Strategic doctrines, training methods, and command culture remained firmly colonial.

Can a nation claim to be truly free when its armed forces are commanded by officers of the former ruler—or any foreign power? Can independence be complete when decisions of war, peace, and military doctrine are shaped by those who once governed the country as subjects? When the Indian Army, Navy, and Air Force continued under British command for years after 1947, was this genuine sovereignty or merely a managed transition?

If freedom does not extend to control over one’s own military, can it honestly be called independence?

Jawaharlal Nehru: India’s PM or Britain’s Safe Choice?

Jawaharlal Nehru was not imposed, but he was certainly acceptable and comfortable for British interests.

- Educated and shaped in British intellectual traditions

- Deeply influenced by Western liberalism

- Skeptical of India’s civilizational ethos

- Reluctant to decisively break from colonial structures

This does not mean Jawaharlal Nehru lacked patriotism. However, it does mean that post‑1947 India remained tied to colonial continuity largely because of Nehru’s deep intellectual and cultural devotion to European thought. Educated in and inspired by England, he equated development with Western modernity, urbanisation, centralised planning, and industrial cities, while viewing India’s village-based civilisation as backward.

Time has proved this assumption flawed. What Nehru sought to replace was infact India’s greatest strength: self‑sustaining, community‑centred, and nature‑friendly villages with decentralised economies and social resilience. By privileging European models over indigenous wisdom, independent India weakened its own civilisational foundations, only to later rediscover, at great cost, the very sustainability it once possessed.

Leaders who represented deeper indigenous resistance and alternative civilisational visions were marginalised, imprisoned, or politically neutralised.

Partition: The Deepest Colonial Wound

India was divided on religious lines, a method perfected by colonial powers worldwide.

Partition was not an accident. It was:

- A strategic exit plan

- A way to weaken the subcontinent permanently

- A method to ensure long-term instability

The human cost was catastrophic:

- Millions displaced

- Over a million killed

- Civilizational bonds violently severed

That wound has never healed.

Kashmir, border tensions, terrorism, and communal mistrust are not spontaneous failures; they are aftershocks of a deliberately fractured independence.

The Psychological Aftermath

Colonial rule ended, but colonial thinking survived:

- English superiority in governance and law

- Suspicion toward indigenous knowledge systems

- Centralised bureaucracy replacing community self-rule

- Laws designed to control citizens, not empower them

True independence requires mental decolonisation, a process India has only recently begun to confront.

Independence Is a Process, Not a Date

15 August 1947 was an important milestone, but not the culmination of India’s freedom struggle.

Real independence demands:

- Decolonised laws

- Indigenous strategic thought

- Civilizational confidence

- Economic self-reliance

- Cultural self-respect

It is a continuing journey, not a completed event.

Erasing the Identities of Enslavement: A Civilisational Imperative

True decolonisation cannot stop at political sovereignty or constitutional continuity; it must extend to the deliberate dismantling of identities imposed during periods of enslavement, whether under British colonial rule or earlier imperial regimes such as the Mughals.

Historians and political theorists have consistently argued that the most enduring form of domination is psychological and cultural. Empires do not merely rule territories; they reshape identities, hierarchies, and self-perception so deeply that the colonised begin to internalise the symbols of their subjugation.

India is no exception.

Across centuries, imposed identities took multiple forms:

- Colonial titles, surnames, and administrative labels were designed to classify, control, and rank Indians

- Cultural and linguistic hierarchies that privileged the ruler’s language and customs over indigenous traditions

- Religious and demographic engineering, including documented instances of forced or coercive conversions and population re-allocations

- Destruction or marginalisation of indigenous institutions like gurukuls, temples, local self-governance systems, and knowledge centres

These were not neutral historical processes. They were state-backed instruments of domination, recorded in colonial administrative manuals, court chronicles, and imperial correspondence.

Yet, in post-independence India, a troubling phenomenon persists: many continue to hold these imposed identities with pride, often mistaking inherited symbols of power for markers of progress. In doing so, they unintentionally erase the pain of their own ancestors who endured humiliation, displacement, cultural erasure, and violence.

When the worldview of the ruler becomes the “common sense” of the ruled, domination no longer requires force. The continued glorification of colonial or imperial identifiers is evidence that this hegemony has not been fully dismantled.

Erasing identities of enslavement does not mean erasing history. It means:

- Rejecting the celebration of oppressive symbols

- Reclaiming indigenous civilisational markers

- Restoring dignity to historical memory

- Aligning national identity with lived civilisational continuity, not imposed hierarchies

A confident nation does not seek validation from the names, titles, or structures bestowed by those who once ruled it through coercion. Civilisational self-respect begins where inherited subjugation ends.

Constitutional and Legal Continuity: The Colonial Skeleton of the Republic

Political independence in 1947 did not dismantle the colonial legal architecture; instead, it largely constitutionalised it. The Indian Constitution, while transformative in ideals, consciously retained vast portions of British-era laws, institutions, and administrative logic under the doctrine of continuity.

Article 372 of the Constitution of India explicitly provided that:

All laws in force in the territory of India immediately before the commencement of this Constitution shall continue in force until altered or repealed.

This provision ensured that the colonial legal framework, designed for control, extraction, and surveillance, survived the transition from empire to republic.

Key examples of this continuity include:

- Indian Penal Code, 1860 (drafted by Thomas Babington Macaulay): A law created to discipline colonial subjects, not empower citizens, retaining broad offences against the State.

- Criminal Procedure Code and Police Acts: Structured around maintaining order for the ruler, not safeguarding liberties of the ruled.

- Land revenue and forest laws: Continued colonial policies that treated indigenous communities as encroachers on their own land.

- Civil service structure: The Indian Civil Service transformed into the IAS with minimal philosophical rupture, preserving its elitist, top-down orientation.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar himself acknowledged this paradox. While defending constitutional continuity for administrative stability, he warned that political democracy without social and economic democracy would remain hollow. The Constitution, he argued, was only a framework; its spirit depended on whether Indians transformed inherited institutions.

Scholars have noted that post-colonial India prioritised administrative convenience over civilisational rupture. The result was a republic governed by laws never designed for a free people.

This continuity explains why, even decades after independence:

- Citizens often fear the State more than they trust it

- Law is perceived as punitive rather than protective

- Governance emphasises compliance over participation

True decolonisation, therefore, requires more than symbolic change. It demands a systematic audit and reform of laws whose DNA is colonial, replacing them with frameworks rooted in India’s civilisational ethos, constitutional morality, and democratic consent.

Recent Legal Reforms: From Colonial Codes to Indian Justice Frameworks

A significant, though long-delayed, step towards dismantling colonial legal continuity came with the 2023–2024 criminal law reforms, where India consciously replaced British-era codes with indigenously framed statutes:

- Indian Penal Code, 1860 → Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 → Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023

- Indian Evidence Act, 1872 → Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA), 2023

These reforms are not merely cosmetic renaming exercises. They represent an explicit political and constitutional declaration that laws drafted by colonial administrators to govern subjects are no longer acceptable for a sovereign republic of citizens.

Key civilisational shifts reflected in these reforms include:

- From ruler-centric to citizen-centric orientation: The emphasis moves from protecting the authority of the State to securing justice, dignity, and rights of citizens.

- Priority to crimes against women, children, and the State: Reflecting contemporary Indian realities rather than colonial anxieties.

- Integration of technology and digital evidence: Acknowledging modern forms of crime ignored by colonial-era frameworks.

- Indian moral and social context: The language and structure consciously move away from Victorian-era assumptions and colonial distrust of the native population.

The very act of replacing Macaulay’s IPC, often described as the most enduring symbol of colonial legal control, carries deep symbolic and substantive value. It signals that India is finally willing to question the sanctity of inherited colonial codes, even when they have been normalised for over a century.

However, these reforms also underline an uncomfortable truth: it took nearly 75 years after independence to begin serious legal decolonisation. This delay reinforces the argument that 1947 marked a transfer of power, not a complete rupture from colonial governance philosophy.

The success of BNS, BNSS, and BSA will ultimately depend on their interpretation and implementation. If administered with colonial mindset, new laws will merely wear Indian names over old habits. If applied with constitutional morality and civilisational confidence, they can become instruments of true freedom.

Completing the Incomplete Freedom

India did not fail in 1947. It was left unfinished.

The British left behind:

- Divided borders

- Colonial institutions

- Psychological dependence

- Strategic vulnerabilities

Earlier empires, too, left scars, through cultural suppression, forced conversions, and demographic disruptions. Acknowledging this is not about assigning collective blame; it is about restoring historical honesty.

Healing requires honesty, not hatred.

To question 1947 and the identities we still carry is not to insult freedom fighters, it is to honour their unfinished dream.

True independence is not when the ruler changes, but when the ruled reclaim their civilisational confidence.

India’s task today is not to rewrite history, but to complete it.